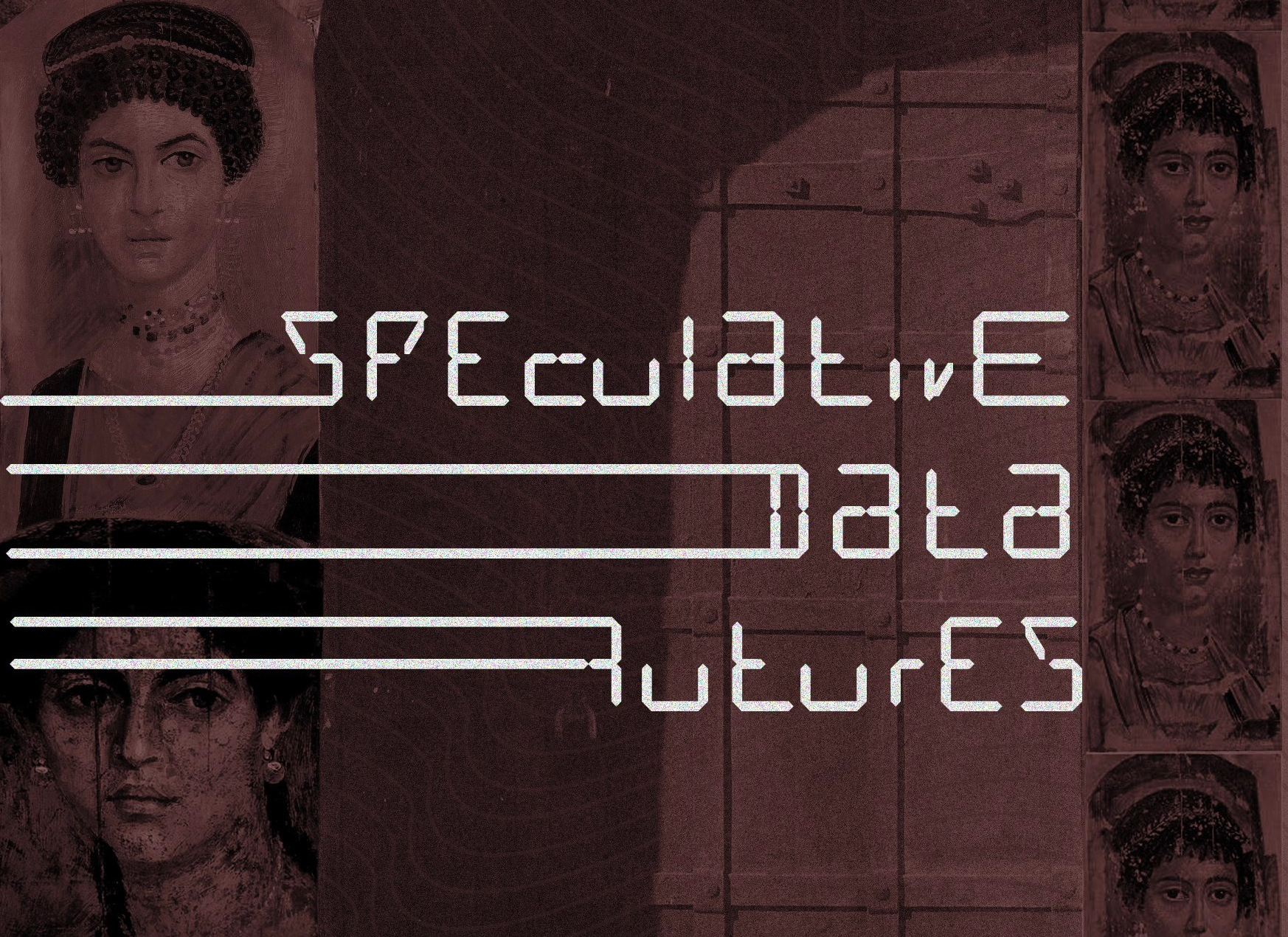

Speculative Data Futures: Karima

Data

Urban development

2021-05-05 18:34:34

2021-05-05 18:34:34

1686

0

1686

0

Welcome to 2030. I am Karima, which means the generous. It always reminds me of my home, Syria, a generous country destroyed by war. I was born and raised in a refugee camp populated by 5000 Syrians. It is not easy to be born Syrian in a refugee camp, especially if you are a woman. Hunger for a loaf of bread in the refugee camp is connected to a hunger for bodies. Lebanon was suffering a refugee crisis with the largest number of refugees per capita in the world and our complaints and objections were not heard there. The international community failed to create a world free of hungry people, as the most powerful countries placed their needs on the top, neglecting the need to end the war that had been devouring my home country for 20 years. In the crowded camp, you don’t find much privacy. The houses are built of simple materials and do not protect you from the eyes or ears of others. I lost the sanctity of my body at an early age. When I was nine, I stopped going to school. I became a “woman” who worked with her mother to clean houses; easy prey. That was me as a teenager: an adult without the right to education and without the right to my body. Yet, I survived. There is always hope: I used my cellphone as a window to the outside world. I mostly used it to chat with people outside the camp, before I realized the power of tutoring applications and social networking. It was not just a mobile phone for me, it was literally everything I possessed. It was through my phone that I saw an offer to register for a committee jointly formed by the Syrian and Lebanese governments to help relieve the aftermath of the Syrian refugee crisis after the end of the war. The commission’s task was to plan and implement the reconstruction of Syria based on insights gathered through personal and open data. They also conducted a large fact-finding mission in which they held referendums over the proposed plans for reconstructions and attempted to put in place a system where people could contact the commission when their proposed plan didn’t suit their preferences. The commission’s tasks were enormous and ambitious, especially with regards to their hopes of achieving accountability and inclusion. I registered to be part of the data collection efforts of the commission and was extremely surprised when I got accepted. I didn’t know much about my country, but I had many images of it in my mind. I knew that it was my responsibility towards my family and the residents of my camp to help rebuild our home. My first mission with the committee was to help collect data from NGOs and the Lebanese security forces about the camp and its residents. The data collected was designed to be used alongside Syrian personal status records as well as data kept at the Syrian embassy in Lebanon, to establish clear lists about the legal status of almost every refugee. In parallel, each person’s genealogy, demographics, and data about geographic origin was also embedded in the created profiles. It was very important to ensure correctness and consistency of the data we gathered. We used every open data set about Syrian refugees directly or indirectly and we could easily find international organisations collecting refugees’ family status, birthdates, political, social, economic background, religious affiliations, gender and sexual orientation, iris scans, fingerprints, information on their mental health, and records of past traumas. The amount of data different NGOs, official parties, and different social media companies had posted on the Syrian open data portal as well as the Lebanese one was extraordinary. I guessed the hard work and demonstrations by open data advocates had paid off. Given the extensive amounts of data collected, the commission was very much aware of the responsibility it had to protect people’s privacy. They suggested guidelines that would make data less readable by human beings: instead of being able to access data and personal information easily, people working on refugee-related projects could interpret results and findings while machines and robots would actually structure and analyze data. During the same mission, we gathered data to assess the economic situations of different refugees as well as their income sources. This data was collected by the Lebanese government from money transfer companies and banks under the new transparency laws which allowed for accessing refugee data, if its purpose was to help in the reconstruction of the country, the data was strictly only used for non-commercial purposes, and if a mechanism was in place that allowed refugees to ask for their data to be deleted upon return to Syria. The law had also been voted into force by all inhabitants of the different refugee camps around the world. Most refugees had gladly voted for the law, they were used to not having much privacy from living in the camp and from their interactions with international organisations. These organisations had demanded to know every intimate detail about some of their most horrific experiences of their lives in order to prove someone’s refugee status, something that often gave them even less rights in exchange. This time they gave someone access to their data, but it was their choice and for a cause they believed in, which made all the difference. It was also the first time they would have the right to delete personal information and data about themselves after returning to Syria. To be honest, I personally didn’t care about my privacy and did not look at the data collection projects as a violation of my personal data rights. On one hand, I believed that the data could help build a better future and on the other hand, when I listened to my parents’ fight at night, I realized I was ready to give up on everything for a chance to live a normal life and to feel happy and safe with my family. So, after getting access to the necessary data, we completed the second milestone and that’s how we arrived at some major achievements for the new Syrian government. The data allowed us to establish: expected demographic sizes of villages and towns when their parents and offspring return to them and their age and gender distribution, statistics on cases requiring legal assistance (not registered with the official state), the skills and income sources of returnees, particularly the labour force, legal provisions, and old employment records of returnees from previous archives. Officials in the two countries, along with international sponsors, were impressed by the strides we were able to make, so the other participants and I were asked to move to Damascus a journey I was very excited to make. For years, I had mostly seen images of my country as portrayed by traditional Western media but returning to it has shed a new light on this depiction: when I arrived at the border point it was clear that a new Syria was born out of the war and its harsh experience with terrorism. At the border, the officer who carried a slim electronic tablet requested my name, which he passed on to a scanner that automatically verified my identity. A few seconds later an access token was generated and inserted as a chip into my hand. The officer announced: Welcome home, miss Karima, this chip has been placed inside you and it carries exabytes of information including emergency numbers. You have also received a copy of your email and personal information registered with the embassy in Beirut. You can download applications to your device and feel free to connect with our assisting drones at any time. The device gives you information about what data we have collected about you and it also includes a simple mechanism where you can flag wrong or missing data, or request to delete personal information. The first thing I downloaded was a private news aggregation application called The Outlet, a start-up created by refugees dedicated to serving refugees. Rather than just sharing news with people, it relies on people to verify the correctness of its news: it uses the social media posts of those who want to contribute to build an internal user profile. Then, the application checks for any information mismatch and generates a trustworthiness score which is visible to users. The whole process is automated meaning people can contribute but no one can manipulate the scores. The more credible the profiles of contributors, the harder it would be to neglect their evaluations of the news. I was one of the contributors in this notion. I selected topics that I thought were important to women in my home town so that they do not get deceived by any fake news or releases they might receive, especially those related to engagement in sexual acts, criminal actions, and terrorism. We shared information about women’s health, sanitation issues, news about politics and economics, information about the new open data rights they had upon returning to Syria. Many returning female refugees were victims in the refugee camp. I had a lifetime opportunity to get over my history and start over again but most of the other women did not get a similar chance. Syria after the war was a hot topic and many people would search for scoops and I did not want any of the women to be hurt or harassed online. The same application hosted an open database for reporting violations against women. This was part of a crowdsourcing project allowing women from across the world to help and to call for action on the spot. Female support groups were online around the clock to show solidarity, listen, and answer any calls. You could choose whether you wanted a real woman or a female robot to listen to you. They were fembots: robots gendered as women. It was hard for some women to open up to human beings and it helped some to speak to fembots instead. Once I arrived in Damascus, I started to work with an amazing team and my war memories started to heal. I moved directly to the Rehabilitation Institute and was responsible for setting up data-driven programs based on refugees’ feedback and memories. I met many women who had been in my place: rape survivors, war-wounded, survivors of harassment and abuse, former female prisoners. I met all types of survivors. I heard testimonies from women who suffered dangerous conditions inside overcrowded accommodation centers. The most vulnerable among them were minors, single women, and unaccompanied girls. Many women also reported violence by their fathers or husbands, as well as by those they met along the migration route to the refugee camp. The long-term physical, psychological, reproductive, and social harms of different types of violence against female refugees are extremely hard to live with. That is why I really admired those women for their strength to go on. The Syrian government was responsible for the Syrian open data portal as well as the data collected in different projects and despite the fact that many had the right to delete data about themselves, the amount of data stored about Syrian refugees was frightening. Many former refugees also did not ask for their data to be deleted. I raised the issue with one of my friends on the project support team, because I knew that majority of the refugees I had met were not aware of how their data was being stored and shared. Apparently, the government claimed that the data was anonymized, and user profiles could not be de-anonymized – but with the amount of data available this wasn’t as impossible as the government had claimed. I was not sure how secure the protected files were and whether this data was shared or sold to third parties. I knew that all parties involved tried hard to implement accountability and transparency measures, but we still had a long way to go. The new government was serious about healing the memories of the war. Our work was divided into more than one program that relied on integrating different open data portals and combining it with real time data in cooperation with more than 100 security apparatuses from around the world in addition to hundreds of universities and medical centers. These groups signed different consents to collect refugee data in anonymous formats and for research purposes only. Partners who uploaded their data had to abide by our data sharing regulations. They were supposed to upload files in a usable format and to name their files according to our standards. We published a manual describing some of the critical characteristics that were mandatory for the data to be open and in order to validate accountability and integrity. It would have been much worse, if had we only received static data files in pdfs or image formats since it is time consuming to scrape these files and restructure them. Using an intelligent machine called Tazakar, meaning remembering in Arabic, a group of open data advocates from all over the world were helping Syrians protect, save and regenerate their old memories and experiences from pre-war Syria. They gathered this information by asking Syrians to share what they remembered about different locations and sites as well as people they knew or were connected to. The tool also allowed anyone to upload media files about the old streets which were still destroyed; stories with family and friends, and descriptions about anything personally precious one could think of. Here, the activists realized that the social norms and cultural barriers might make it harder for women to share their images or personal data. Men on the other had less limitations to the data they could upload and images they could share. That is why, the activists designed a secure ciphering system that gave users the option to encrypt the data as to prevent its disclosure to any party. This way it would only be used to train artificial intelligence algorithms in the tool. This data is used to generate open knowledge for others to use as it would be very helpful in renovation activities being designed by engineers. Tazakar was one of the impressive open data celebrations which helped me live in a house that my parents once lived in. The robots used the data collected about us to rebuild it from scratch, saying the resemblance level exceeded 70 percent. But my mom says nothing will feel the same.